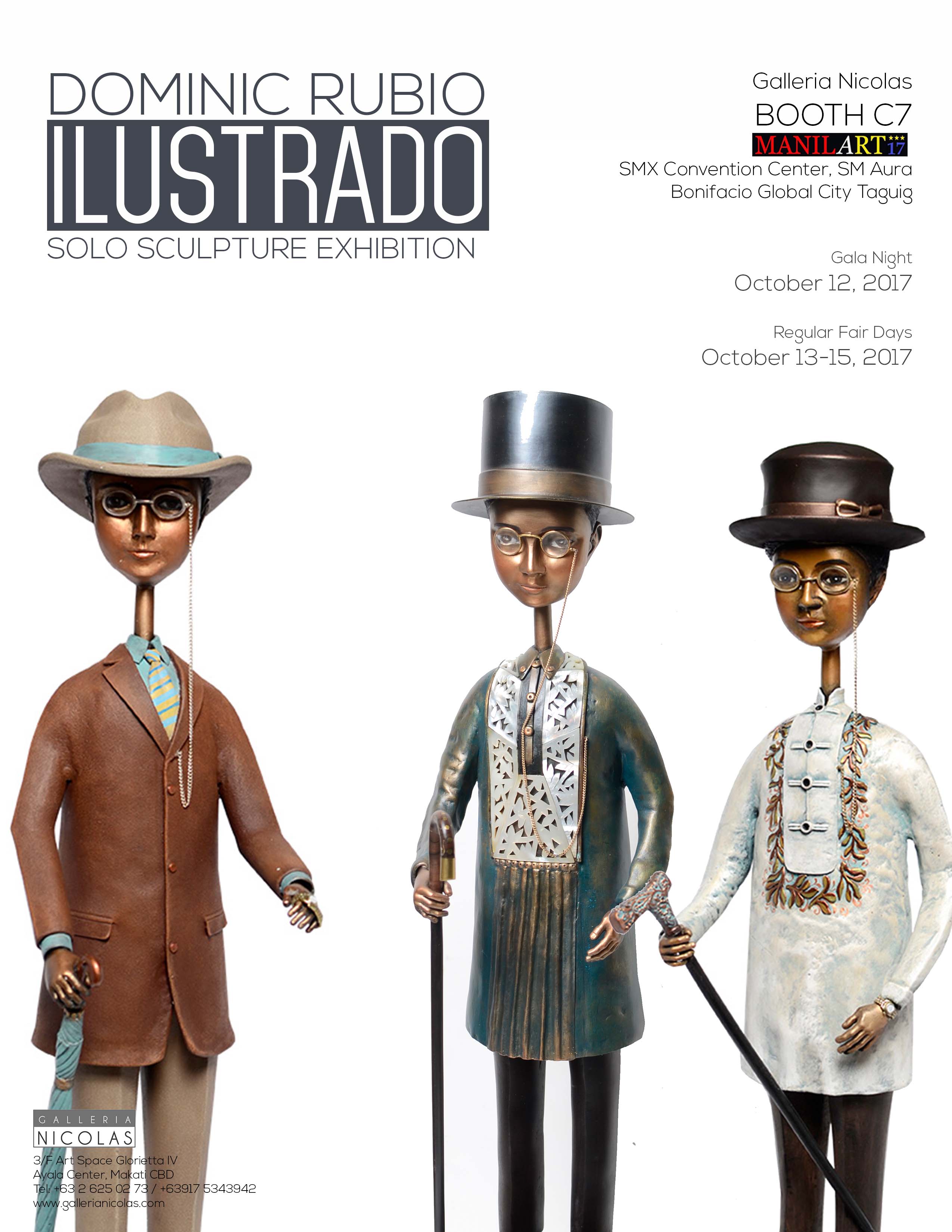

Ilustrado: Rubio’s Filipino-ness Taking Off

By Kara de GuzmanIn the sixteen years since he entered the scene as a professional artist, mounting his first solo exhibition “Grand Expressions,” Dominic Santos Rubio has steadily built up his repertoire and reputation. His iconic “people type” oil on canvas paintings depict Philippine identities of a past age: inquilino sharecroppers, principalia landowners, compradores, etc., airily milling about an Old Manila milieu. Now, Dominic returns to his roots as a Paete-born artist, unveiling a new stylistic exploration in an entirely different medium – brass sculpture.

Trained in the commercial arts in the University of Santo Tomas, Dominic worked in advertising and was an artist-in-residence at Pearl Farm, Davao del Sur before catching his break in 2006 – debuting what was to become his signature style. Readily recognizable, his most famous iconography charmingly features larger-than-life subjects towering over quaint miniature background renderings of 19th century Manila panoramas. Similar to the forced perspective photography technique, Dominic places the doll-like figures close to the edge of the picture plane, while depicting the background as dramatically small in comparison. Set against stark monochromatic skies in bold crimson, pale yellow, and muted beige, the artist renders romantic dioramas of what used to be Binondo, Tutuban, Escolta; families attending Sunday Mass in Malolos Church, riding a kalesa down Paseo, or a mestiza de sangley riding a bicycle. Always, Dominic’s figures express a disattached countenance, sporting uniform Sinitic features while they float about on Lilliputian limbs. Their dress, owing to the influence of Damian Domingo’s tipos del pais, seem to hover half a foot or so above their bodies, lending them an inflated ethereal quality that has become the artist’s distinctive mark.

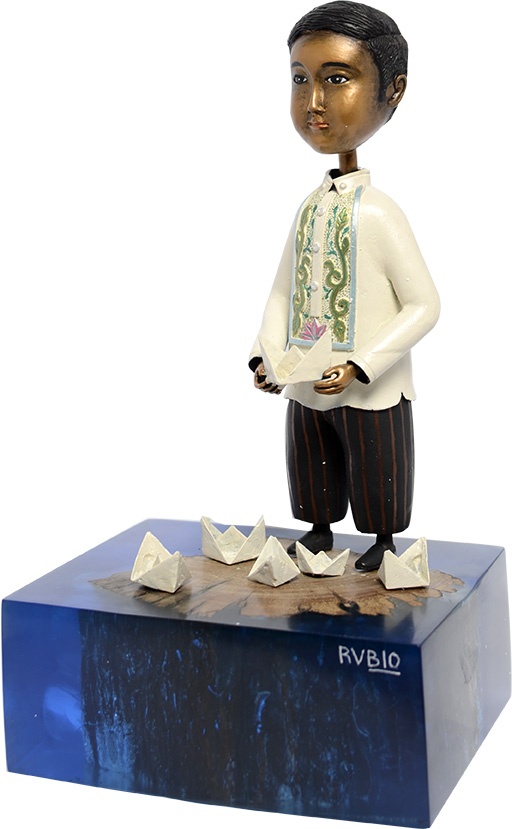

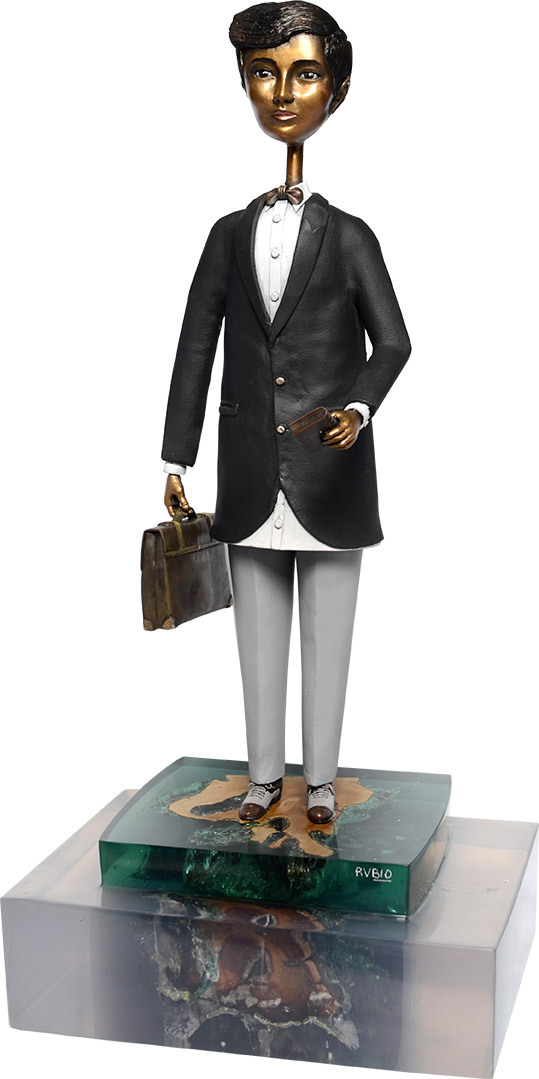

His new series of artworks, a leap beyond the boundaries of two-dimensional depiction into three-dimensional sculpting, is an invigorating new step for Dominic Rubio. Hailing from Paete, Laguna – a municipality known for its artisans and carvers of po-on – Dominic fulfills a long-time aspiration by elegantly translating his strong linear style into the malleable medium of brass. The sculptures feature the familiar social and economic diversity of the Philippines during its time as “The Most Beautiful City in the Far East.” “Crisostomo” is a well-dressed businessman in a top hat and barong decorated with capizdetail; the “Sabongero” is a moustachioed man in a salakot holding a handsome fighting cock; a “Bagoong Vendor” is accompanied by three pots – two on the base and one balanced on the head – and garbed in a homely baro’t saya ensemble; while a family of three candidly habitate “Paseo.”

While still rendered in his people type style, comparing Dominic’s painting and sculpture unearths dynamic changes in his work’s metanarrative. The elongated neck, an allegory for nationalistic pride, is present in a more balanced composition; the minute changes in proportion lending the Rubio figure more harmony. Their complexions are a textured dark brown, befitting of brass’ bright, gold-like appearance that adds a layer of depth to the Filipino’s underrepresented sun-kissed color. Following in the tradition ofminiaturismo, Dominic’s sculptural figures sport intricately decorated accouterments: a woven basket, an embroidered purse, and a stray dog to name a few. As with its use in the 19th century, these minute details are indicative of the subject’s social class and identity constructed through societal roles and the kind of labor expected of them. These markers, forgotten yet familiar, evoke a strange nostalgia; the particular people, places, and professions they characterize are long-gone but the economic stratification remains, as if a specter of the present was precognized in the past, and vice versa. Today, vestiges of Old Manila are hidden in plain sight, but its legacy can still be felt tangibly in our everyday life.

Finally, the most notable difference between Dominic’s painting and sculpture is the absence of the miniaturized panoramic background that contextualizes and activates his paintings’ giantism effect. By casting his figures in solitary profile Dominic takes away the lavish backdrop, yet still the aura of the Pearl of the Orient remains – albeit not unchanged. These characters, extant in the Filipino's collective imagination, carry metonymic worlds on their shoulders without needing to say a word. But by removing them from their 19th century plazas, Spanish/American architecture, and picturesque bahay-na-bato, and literally transplanting them into the present, Dominic allows the nostalgic to enter the contemporary.

As a staunch advocate for the preservation of national cultural heritage, Dominic’s reinterpretation of Old Manila – into both two- and three-dimensional visual media – makes concrete an abstract history. He accords this past with renewed significance while reinjecting its imagery into collective living memory. By depicting pre-war Manila, especially as brass sculpture, not only does Dominic insure that Manila’s golden years will be remembered, he also reforms heritage into a malleable construct. His latest foray into sculptural form is an homage to the colonial Filipino identity carefully balanced between native and imperial, classic and modern; posing questions of identity in a more approachable place. The brass sculptures take ownership of a “traditional” Philippine history as 3-D models, but also as caricatures, opening up a conversation on national identity and Filipino-ness past iconography, essentialism, and primitivism.

Dominic Rubio revitalizes his roots, repertoire, and relevance in this new series of brass sculptures. As tangible recreations of Old Manila, the new series calls to mind similar efforts to adapt and reuse old structures, like the Luneta Hotel and Casa Tesoro in Ermita, the Malate Church, and the much-anticipated Metropolitan Theater. These historic sites and structures are strategically altered in order to strike a balance between identity preservation and utility; Dominic’s sculptures perform much the same. While they are recreations and re-presentations of nostalgia, they are also active expressions of hope for the preservation and re-production of Philippine cultural heritage.